strega nona's pasta pot

DePaola, Tomie, Strega Nona: An Original Version of an Old Tale. 1st Little Simon board book ed. New York: Little Simon, 1997. Cotsen Collection, Moveables 37931

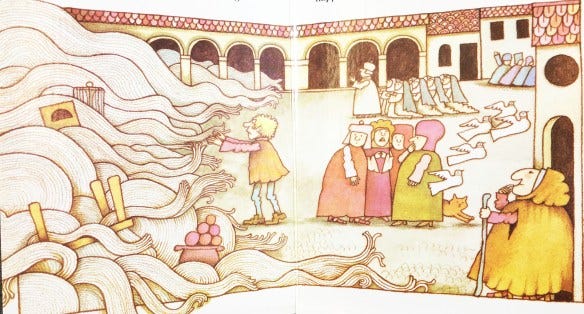

Abundance is the province of witches. Setting aside Macbeth’s Weird Sisters and the Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West, better known for their powers of divination and hordes of winged monkeys, most tales of witchcraft (or maybe just the tales I like) center the act of conjuring, the making of something from nothing. A coin appears in an empty palm; a potion awakens two strangers to the possibility of love. Or, in the story of Tomi dePaola’s Strega Nona, a witch’s magical cauldron generates infinite amounts of pasta. So much pasta, it floods the streets and sweeps up furniture into a carbohydrate-laden tsunami.

We kept a copy of Strega Nona at home, nestled between Stellaluna and The Runaway Rabbit. I would flick through the pages until landing upon the drawing of a provincial Italian town awash in spaghetti. That image triggered an instant dopamine hit in my tiny child brain. So this was abundance.

Unlike the magical pasta cauldron, real-life good things came with constraints, upper bounds arriving long before my wants had been sated. I wanted more strawberry ice cream, more Saturday mornings at the playground, more hugs and kisses, but there was always a limit at which someone would shake their heads and tell me, No more. Yet the good things were so truly good that I couldn’t imagine not wanting more. Was real satisfaction—the possession of boundless amounts of something worthy of possession—possible only in fairytales?

Strega Nona’s infinitely giving cauldron of pasta was on my mind again in May, when I spoke to one of my college roommates on the phone. “I’m a bottomless pit of need,” I told her, feeling like the cauldron’s exact inverse. “I want more and more.”

“I don’t see you as a bottomless pit of need,” she replied very kindly. But I am. Most pathologies of mine reduce to the same fear: that all things good are scarce and the implicature, that anything joyful must come to a close. The well runs dry.

When presented with the promise of complete wish fulfillment, we are predisposed to suspicion (see, e.g., Billie Eilish’s “everything i wanted”). Our mistrust is partly grounded on the belief that our wants belie our needs, that they are mere smokescreens shielding us from murkier, more ineffable desires. If our wants were met in full, we would see them, finally, under the harsh glare of day, standing before us in all their smallness and triviality. And we would still feel a lack. In an old Dear Sugar column, “Monsters and Ghosts,” Cheryl Strayed recounts a childhood visit to her father’s home, the first time they had seen each other in five years:

One afternoon my father made popcorn and told me I could have as much butter as I wanted on it. “More,” I kept saying as he poured the melted butter over the popcorn in my very own gigantic bowl. “More,” I persisted until the entire pile of it deflated like a popped balloon under the weight of all that liquid. I don’t know what possessed me. I couldn’t bring myself to stop saying more until it was ruined. In the end, there was nothing to do but throw the entire sodden mess in the trash.

Strayed concludes her anecdote with the recognition that her desire for an obscene amount of melted butter unspooled into a deeper absence, the empty space where her father should have been. “He was, for once, trying to give me everything I wanted and I was trying to get everything I needed,” she acknowledges. “[A]nd it was way too late for either one.”

This is the hard part about real-world abundance: for one person to receive, someone else must provide. Outside of the witchy realm of Strega Nona, where spaghetti appears without anyone asking for it, the desire for an unending more requires someone capable of meeting that desire. Capitalism’s abstractions might shield us from this reality—we might, for instance, turn away from the workers manufacturing our fast fashion, or the ecosystems destroyed and wars fought to secure our country’s supply of fossil fuels—but much of what we are taught to want comes at real cost borne by other bodies. And these demands are only uncertain approximations of the real lack.

The tragic impossibility of true abundance also unfolds on a scale far smaller than capital-c Capitalism. Folktales are replete with characters—particularly women—whose abundance comes not from a magical cauldron but from a personal reserve at once finite and infinite. The Crane Wife and the Giving Tree simultaneously draw upon their physical bodies (limited) and their capacity for love (boundless) to meet the ever-rising demands of the men in their lives. The Crane Wife’s husband wants more and more bolts of splendid silk; she plucks her own feathers to weave them. The Giving Tree gives her branches, then her base to build a house and a boat for her boy. Unlike Strega Nona, the Crane Wife and the Giving Tree’s capacity to give is no match for man’s capacity to want, which invariably grows to exceed existing supply.

In college, one of my creative writing teachers told my class to give our characters something to chase after, a fixation. “No one moves through the world wanting nothing,” he said. In his view, we are made real by our desires. But the Crane Wife and the Giving Tree are made real not by their own desires but by their ability to fulfill someone else’s, their identity defined only in relation to someone else’s want. Sabrina Orah Mark’s stellar essay in the Paris Review Daily, “Fuck the Bread. The Bread Is Over,” suggests something similar, that fairy tale characters are defined exclusively by their function, their ability to perform a task at hand. “If you don’t spin the straw into gold or inherit the kingdom or devour all the oxen or find the flour or get the professorship, you drop out of the fairy tale, and fall over its edge into an endless, blank forest where there is no other function for you, no alternative career. The future for the sons who don’t inherit the kingdom is vanishment,” she writes. Form and function collapse into one. The Giving Tree and the Crane Wife, after all, are named for the roles they perform, that of giver and of wife. The Giving Tree, reduced to a stump to sit upon by the story’s close, is blind to her own tragedy (“And the tree was happy”), content to fulfill her function.

“Wanter” and “provider” are both functions, not forms, and the men in these tales—those greedy boys who want apples, then branches, then the tree entire—are no freer or more fully realized than the women. They, too, are tethered to their functions. Desire deprives all participants in its zero-sum economy of the opportunity to transcend this bleak calculus.

How much of my life have I spent wanting things, or providing them, or wanting people to give them to me, or wanting to be wanted, every transaction weighed and measured, each fleeting feeling refracted through the dyadic relation of A wants X from B? The dates and dinner parties, the fancy resume lines, and exams, and awards. Then in March and April and May, my world shrunk to the size of a room. It was a joy just to be out in public, buying a head of broccoli or a bundle of carrots. Like a character in a fairy tale, I undertook silly little tasks, but instead of capturing a kingdom or chasing a prince, I was just trying to stave off the beast at my back. Still the wants hummed, loud as ever—louder—wanting to be in love, for the world to return to normal, no, for the world to radically transform, and I was ready to give it, whatever was demanded of me, not sure what to give or to whom to give it. So that was May, then June, July. How much time I’ve spent chasing or being chased, when I could have just been. This is what I found so striking about that pasta cauldron: it signaled the possibility of abundance requiring no production costs and no purchase price. A bestowal unasked for, requiring no sacrifice.

This past January, I visited my paternal grandmother, my amah, in Taipei. She has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s for the better part of the past two decades. Given my infrequent visits, biannual at best, I’m not always sure who I am to her. What is the function of a granddaughter an ocean away? Still, in January, I sat next to her on the couch, and she clasped my hands in hers and smiled. Hen gaoxing, hen gaoxing, she repeated, her hands so small and powdery soft around mine. I’m so happy. I’m so happy.

I asked my dad what usually happened after these visits, if she could remember the fact of our being there, with her, at all. He said, “She can’t remember, but sometimes the happy feeling lingers on for days.”

If I had any say in the matter, this is what I’d like to be—a formless and functionless abundance, a lingering feeling holding fast to my loved ones from this far away.